The First Published Method for the Bass Clarinet

The First Published Method for the Bass Clarinet

- A. P. Sainte-Marie’s Mèthode pour la Clarinette-basse… of 1898 -

and a Brief Survey of Subsequent Didactic Works for the Bass Clarinet

by Thomas Aber

As a member of the clarinet family, the bass clarinet has until recently had little solo repertoire and virtually no didactic material specifically devoted to it. Outside of its gradual adoption as a member of the woodwind section in orchestras and military bands, the history of its early use is very sketchy. Very little is known about solo repertoire for the bass clarinet and the musicians who may have performed on the instrument during the 19th and early 20th century. Even less is known about how those musicians may have learned the techniques specific to mastery of the bass clarinet during this time. Thomas Lindsay Willman (1783?-1840), the English clarinetist who performed the bass clarinet concertante part in Sigismund Neukomm’s aria,” Make haste, O God to deliver me,” is a notable exception in that there is a record of his performance in April of 1836 of a piece which is still extant.1 The next bass clarinetist known in combination with specific, still surviving repertoire he performed is A. Pierre Sainte-Marie. Pierre Sainte-Marie served as the bass clarinetist with the orchestra of the Grands Concerts Colonne in Paris and with the Concerts Classiques de Monte Carlo during the last years of the 19th century.2 Several brief, lyric pieces with orchestral or piano accompaniment written for him were published by Evette et Schaeffer in Paris between 1897 and 1902.3 These, along with four short pieces published by Merseburger and C. F. Schmidt in Germany between 1898 and 1903, are among the earliest known commercially published solo works for the bass clarinet. In addition to inspiring music by several composers, Pierre Sainte-Marie is also the author of the first published method and, for that matter, the first didactic material of any sort for the bass clarinet.

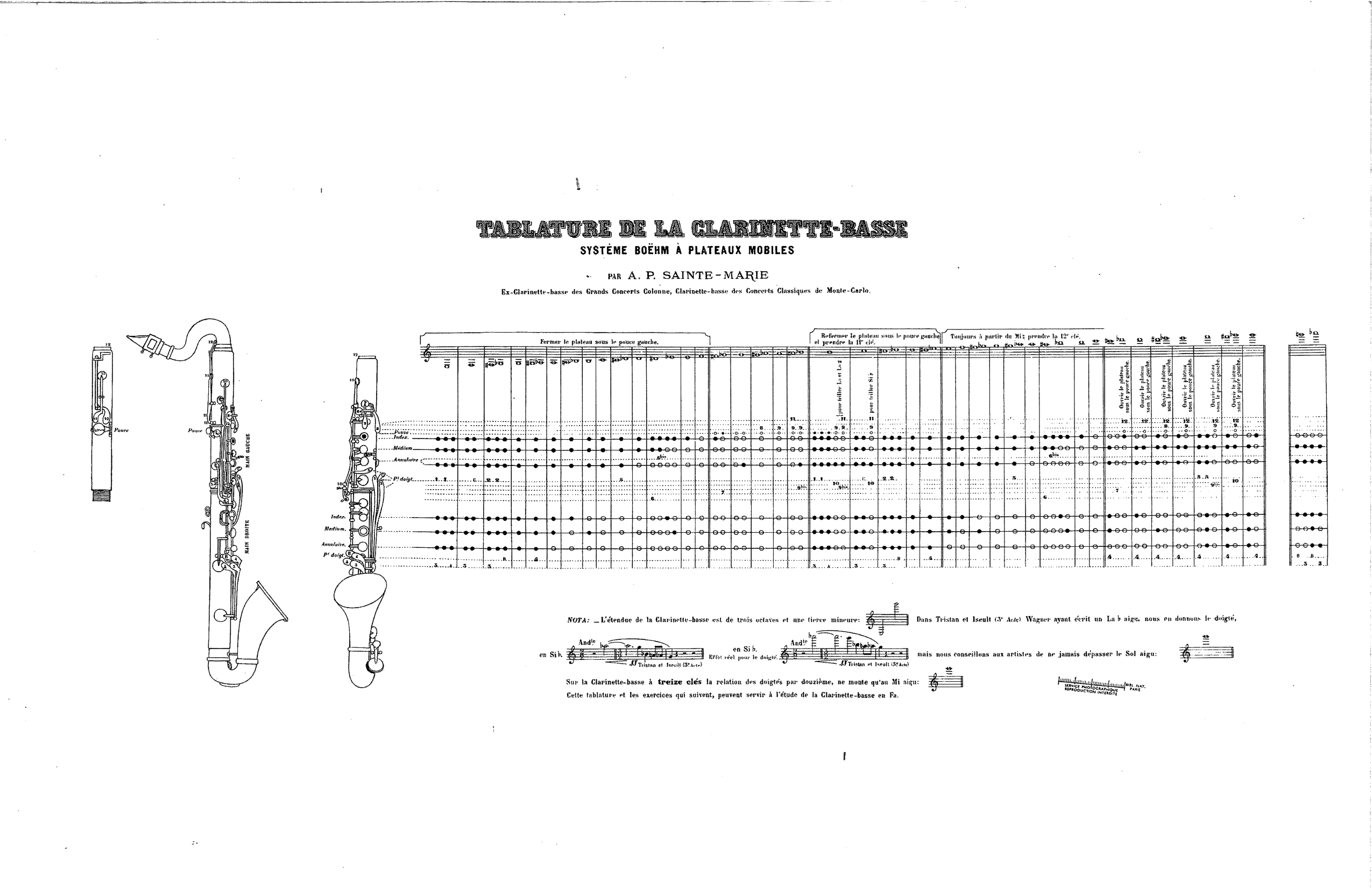

Sainte-Marie’s 20-page Mèthode pour la Clarinette-basse, á l’Usage des Artistes Clarinettistes, avec l’indication des doigtés pratiqués, which includes a clear fingering chart, was published in Paris by Evette et Schaeffer in 1898. It was written to be used by clarinet-artists, thus skilled musical performers who had already acquired technical proficiency on the soprano clarinet. It is primarily a guide to practical fingerings for the bass clarinet in cases where these fingerings would differ from those employed on the soprano clarinet.

Page one of the Mèthode is a brief preface which describes the bass clarinet as the least familiar of the instruments of the orchestra and military bands. The preface compares the bass to the soprano clarinet as the organ would be compared to the piano. It states that few artists have attained their desired results in study of the bass clarinet, because at the time of the Mèthode’s publication there were no materials available dealing with the specific issues and technical difficulties of the instrument. The preface is followed on page 2 by a three paragraph history of the early forms of the bass clarinet, crediting A. Buffet jeune with the first truly usable bass clarinet. Buffet’s improvements to an instrument made by Dumas, chief jeweler of the Emperor, in 1807 allowed Isaac Franco Dacosta to brilliantly perform the now famous bass clarinet solo in Meyerbeer’s opera Les Huguenots in Paris in 1836. Thereafter, according to the history, Adolphe Sax and A. Buffet jeune together made further improvements to this instrument, effectively inventing the bass clarinet in use at the time of the Mèthode’s publication.4

The instructional portion of the Mèthode begins with a preparatory page of text describing care of the instrument, playing position, and recommendations regarding reeds and mouthpiece. To a modern reader attention to the integrity of the instrument’s long metal rods, as well as the need to store and transport the bass clarinet in a case, rather than a soft bag, seem self-evident. However, this may not have been common practice with many of the less mechanically complex instruments in use in 1898. Sainte-Marie recommends playing seated and using a neck strap to support the instrument. He recommends the use of a rubber mouthpiece, paired always with light reeds. This is followed by “First Tones to Study,” a page of text combined with musical examples.5 These tones are D, E-flat, and E in the clarion register, the tones at the transition between those controlled by the bass clarinet’s lower register vent and those controlled by its upper vent. The need for two register keys to adequately vent the bass clarinet’s upper register presented a significant technical complication for most performers until the 1930s, when the use of a single key for an automated operation of the two vents became commonplace.6 After explaining the two vent keys controlled by the left thumb and the proper way to switch between them, Sainte-Marie provides two pages of exercises to habituate the thumb to the two octave (sic) keys. The exercises consist of four-note ascending and descending scale passages, written as 16ths, in every possible tonal configuration and starting on each chromatic tone within the range from A in the throat-tones to D-flat in the clarion register. He also includes four-tone ascending and descending chromatic passages staring on D, E-flat and E in the clarion register. He describes tones in this range as the “muted tones” of the bass clarinet and says that these exercises to develop purity of tone and fluidity in this range are the most important exercises in his Method. Each of the measure–long passages indicates with a number and brackets which of the notes require the upper vent to be opened.7

Sainte-Marie’s next major topic is the altissimo register, which he introduces with three pages of brief scalar exercises for “the left hand and high notes.” The fingerings he recommends for the tones from C-sharp through G-sharp (the highest pitch included) differ greatly from those commonly used on the soprano clarinet. Bass clarinets in the late 19th century presented several challenges unfamiliar to performers on modern instruments. Among these was presence of an open ring on the tone hole controlled by the player’s left index finger. Page 6 of the Mèthode is an advertisement announcing the recent beneficial addition of a plateau key for this finger on the bass clarinets made by Evette et Schaeffer. This greatly facilitated performance through much of the instrument’s range, but eliminated control of the venting for the altissimo register by the index finger, as the small speaker-aperture, which is now a feature of this plate, was not present. Sainte-Marie therefore recommends the use of overblown throat tone fingerings for the tones up through altissimo E. For F and F-sharp either this type of fingering or “long” fingerings with the index finger closed are recommended. Only G and G-sharp are again similar to the standard soprano clarinet fingering. All the fingerings for altissimo tones are clearly indicated by diagrams directly under the notes. Study of the altissimo is completed by an exercise regarding production of legato intervals.

The Mèthode, which is generally comparable to the third division of the Baermann’s method for soprano clarinet, offers exercises on the chromatic scale, major and minor scales, and major and minor arpeggios throughout the instrument’s range from low E to altissimo G. Sainte-Marie recommends practicing the scales and arpeggios in a moderate tempo in order to emphasize the bass clarinet’s “religious and solemn, rather than light and rapid character.”8 All the exercises have fingerings indicated for the altissimo register notes and proper choice of register key, but give no indications of fingerings otherwise. The Mèthode concludes with brief descriptions of French and German notational systems and suggestions to aid in transposition of music written in A by use of moveable clefs. He goes on to say that “as there are no voluble passages written for bass clarinet and in a slow tempo a B major scale is as easy to play as a C major scale, we recommend that performers acquire a bass clarinet in B-flat equipped with a low E-flat …”9 This indicates that Sainte-Marie regarded the use of two bass clarinets, one pitched in A, as impractical and also that instruments in B-flat with a half-step extension to low E-flat were becoming available in France at the time of publication, though Sainte-Marie makes no other mention of this extension in his Mèthode. Saint-Marie’s work has certainly been superseded by methods and studies currently available and the technical issues it addresses specifically are no longer critical challenges. However, the very appearance of the Mèthode constitutes a significant step in the development of the bass clarinet as an individual orchestral and solo instrument.

More than fifty years appear to have passed before the publication of another instructional method for the bass clarinet. In 1952 Himie Voxman’s Introducing the Alto or Bass Clarinet was published by Rubank in the United States. Between 1962 and 1968 William E. Rhoads wrote or edited six volumes of studies for the alto and bass clarinet published by Southern Music, which dealt with specific technical issues of these instruments. These include his Technical Studies, Etudes for Technical Facility, and Advanced Studies from Julius Weissenborn. All of these works had students in school instrumental music programs as their primary audience.

Interest in the bass clarinet as a solo instrument has grown exponentially in recent years and, as a result, so has the quality and quantity of teaching materials for the instrument. Spurred by the efforts of virtuosi such as Josef Horak, Harry Sparnaay, Henri Bok, J. M. Volta, and others, composers have created a substantial solo and chamber music repertoire for the bass clarinet and have made high technical demands on its performers. The musical vocabulary of these works, such as their extremely wide range and frequent use micro-tones, slap-tongue, and multiphonics, requires a specialized technique. The Dutch bass clarinetist Henri Bok addressed these issues in his New Techniques for Bass Clarinet (1989, rev. 2011, www.henribok.com). Jean-Marc Volta, formerly principal bass clarinetist with the French National Orchestra, published his La Clarinette Basse in 1996 (Paris: International Music Diffusion ). This work could be considered a direct descendent of Sainte-Marie’s Mèthode, but on a much grander scale. It deals with traditional playing techniques throughout the entire range of the modern instrument to low C and includes detailed exercises on sound production, use of the tongue, digital dexterity, and transition between registers. Along with diagrams concerning fingerings, oral formation, and tongue placement, as well as technical exercises, it includes orchestral passages paired with each topic. In 2007 the firm Farandola Editrice of Pordenone, Italy began a catalogue of didactic works and solo repertoire for the bass clarinet. It includes studies by Paolo de Gaspari, Sergio Mauri, and Martin Roth. A complete listing of their publications can be found at www.Farandola.eu. Harry Sparnaay’s The Bass Clarinet – a personal history, published by Periferia Sheet Music, Barcelona in 2011 is not a method in the traditional sense, but is a very useful essay about many aspects of playing the bass clarinet and about the development of its repertoire. In addition to this work, Harry has also written Daily Chromatical Studies for the Bass Clarinet, also published by Periferia. Useful as well as musically enjoyable studies for the bass clarinet have also been written and published in recent years by Patrice Sciortino (Sillons, Paris: G. Billaudot, 1996), Pedro Rubio (Estudios para clarinet bajo vol. I, vol. II, www.bassusediciones.com, 2004-6), and Sauro Berti (Venti Studi, Milano: Edizioni Suvini-Zerboni, 2007).

Bibliography

Aber,Thomas Carr. “ A History Of The Bass Clarinet As An Orchestral And Solo Instrument In The Nineteenth And Early Twentieth Centuries And An Annotated, Chronological List Of Solo Repertoire For The Bass Clarinet From Before 1945.” D.M.A. diss., University of Missouri at Kansas City, 1990. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International.

Kalina, David Lewis.”The Structural Development of the Bass Clarinet.” Ed.D. diss., Columbia University, 1972. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International.

Sainte-Marie, A. Pierre. Mèthode Pour La Clarinette-basse, á l’Usage des Artistes Clarinettistes, avec l’indications des doigtés pratiqués. Paris: Evette et Schaeffer, 1898. A copy of the work is held by the French National Library.

Endnotes

1 Thomas Carr Aber, “A History Of The Bass Clarinet As An Orchestral And Solo Instrument…” (Kansas City: The University of Missouri at Kansas City, 1990), 77. www.circb.info/?q=node/10006

2 A. Pierre Sainte-Marie, Méthode Pour La Clarinette-basse… (Paris: Evette et Schaeffer, title page).

3 Aber, ”A History,” 105-107.

4 Sainte-Marie, Méthode, 2.

5 Sainte-Marie, Méthode, 5.

6 David Lewis Kalina, “The Structural Development of the Bass Clarinet” (New York: Columbia University, 1972) 184.

7 Sainte-Marie, Méthode, 8.

8 Sainte-Marie, Méthode, 13.

9 Sainte-Marie, Méthode, 20.

About the Writer

Thomas Aber, D.M.A., is a native of Kansas City, Missouri. His study of the bass clarinet has led him to the Juilliard School in New York and to Amsterdam, where he studied with Harry Sparnaay on a Fulbright-Hays grant. During his stay of several years in The Netherlands he was a prize winner in The Gaudeamus Foundation International Competition for Interpreters of Contemporary Music. He has given American and/or world premieres of numerous works. Bass Clarinetist with the Omaha Symphony since 1990, Dr. Aber is also a founding member of newEar, Kansas City’s ensemble for new music and of the Myth-Science Ensemble.